Nick Jacobsen - daring greatly.

Big Air is not a sport for the faint-hearted. You're alone in the sky in massive conditions, relying on just your skills and your kite. North Team Rider Nick Jacobsen is well known for his 'daredevil' antics. As a successful extreme athlete, he has developed a healthy methodology for managing and overcoming fear. We talk to the Danish pro-kiter as he celebrates his third Big Air season launch with North about how he tackles fear and what it takes to stay at the top of your game for more than six years.

Everything you want, is on the other side of fear.

"Every time there is fear, you should listen to it. And you can either make it shut up, or you can challenge it in a way that feels right."

Red Bull performance coach Gary Grinham says, "fear causes a negative mindset. It instils in you elements of doubt, reluctance and lack of trust". Nick comes into the game well prepared to eliminate that mindset - for him, risk assessment and visualisation is important.

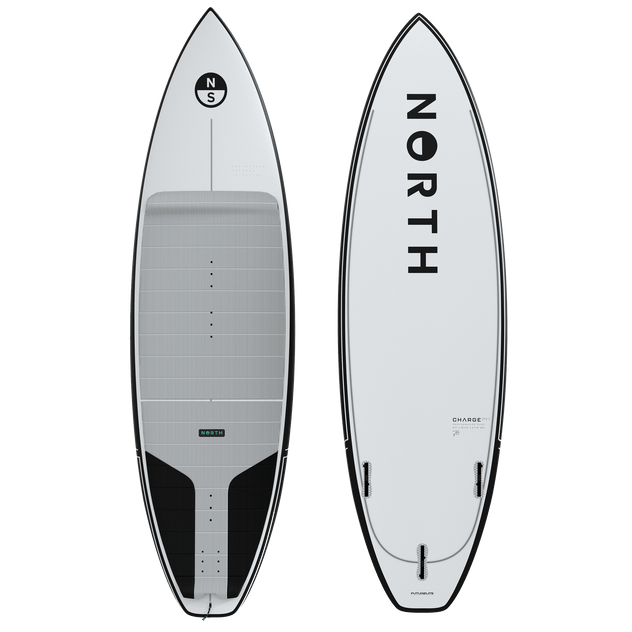

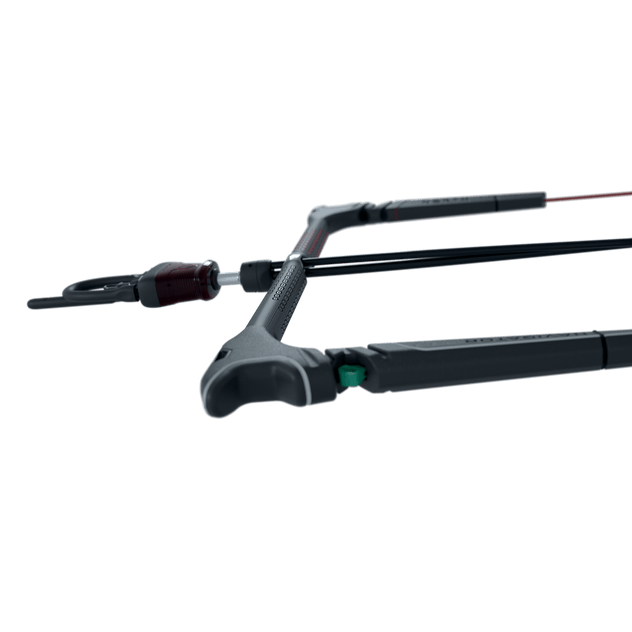

"If I don't see it happening, then it's not going to happen. I trust my equipment 100%. There are so many factors that could go wrong, but being with a brand like North eliminates that thought. If I know I've done my homework, then it's down to trusting my own skillset, trying to visualise what I have to do.

"I wouldn't go somewhere in the world and say, "that's a cool building. Let me take the lift up with my gear and jump off it". I would never do that. I'd take the lift without my gear, but with my notebook. I'd try and calculate as much as possible, then team up with my friend, who is good at analysing wind conditions. That's the process I usually go through. I'm incredibly nerdy with the stuff that I do, and I know the risks.

"But I think the fear that comes from your surroundings is different to the fear that comes from within. I had to study this quite a bit to understand how my brain worked, and my conclusion was that every time there is fear, you should listen to it. And you can either make it shut up, or you can challenge it in a way that feels right.

"I always get frightened when I'm standing on top of a building, so I'll take it in for about a minute, sit with it, then review it. Ask what it is, where it comes from, is this a type of fear I've had before, or is it a new type of fear? If it's a new type of fear, I won't jump. I'd need to examine it and figure out what and where this fear actually comes from.

"I've only met with fear like this a few times. Then I've put my kite down, looked at it multiple times, teamed up with people in that field who know how to analyse wind near buildings, near trees, you know, updrafts or whatever might be. Once I have the knowledge, I'll go back to it."

This kind of rationalisation, defined by Dr Pippa Grange in her book Fear Less as "using logic and statistics to take yourself out of your fear", is a common technique used by Nick and other kiters to overcome fear.

"Everything is very planned, even though it doesn't look like it. I like putting stuff online that provokes and makes people think that I'm crazy. But I would never do something that didn't FEEL right.

"I know it can seem crazy when you list what I’ve jumped with a kite, but I take great honour in being in control and assessing the origin of the occasional fear, so when I do it - It never feels crazy.

"I've gotten a bunch of email and Instagram messages from parents – they're like; 'you shouldn't do this, it's crazy, and you're not even wearing a helmet! My son looks up to you, and now he wants to jump off things.'

"I try to put myself in their shoes, but it's difficult for me. When I look at Travis Pastrana, I'm like, HOLY BANANAS, I will never try and do something like that in my whole life because I know my limits. I can't even do a wheelie on a dirt bike, so why the hell would I try to do a double backflip? If you don't know your limits, that's when it goes wrong."

In 19 years of kiting, Nick's only broken an ankle and a finger. "I don't know if I've been lucky, but if anything happens to me during those "crazy" acts, then it would be pretty fatal. You wouldn't just break an ankle. But I do the risk assessments and calculate everything well.

I think I'm the opposite of crazy. But that's the brand side of being Nick Jacobsen.

"When I get home and cook dinner for my girls, my girlfriend Marie, and her 8yo daughter (who has to be in bed by 8.30pm), I'm so different to that maniac flying around on a kiteboard. If you can't compartmentalise those different aspects in your life, then it becomes a maze, where you don't know what's up, what's down. Without structure in my life on a day-to-day basis, I sort of lose myself. Before I met Marie, I was just this single professional kiteboarder flying around. I didn't have any responsibilities other than being sponsored by people and having deadlines to meet. But now, this is actually a job; it's not only passion. It's what puts food on the table and fills my car up with gas. Taking all these things slightly more seriously really helped me a lot.

Nick lives on the beach, in a small village just north of Copenhagen, close to his Mama's house. He and Marie are expecting a baby boy in December. "I think it's going to change a lot of things – hopefully not all the good things, but I think not. Already my relationship with Marie's daughter has changed me – but only in a better way. I talk to Jesse a lot about it, and I can't wait. I think it's going to be such a positive anchor in my life. But I think I will ask myself twice, no, ten times before I actually do stuff."

What scares Nick most? Losing control of something he thought he had control of.

"When I'm taken by surprise, like 'holy shit, I didn't think about this," - that really scares me, because the consequences, the things that could go wrong, are things I haven't thought about. Underneath that is the idea of other people looking at me and telling me, "I told you so". You shouldn't have done this. Usually, I don't give a shit what people think of me, but if something goes wrong, then how the hell do I justify my next big stunt? I would lose respect from people I work with, friends who trusted me and my ability to do what I do."

Nick's words describe some universally human fears. If you peel the layers back, three big ones come to mind – the fear of not being loved, failure, and not being 'enough'. Nick's ability to overcome these fears as an athlete has helped him prepare for other challenges in life.

"I think being able to lean against something you're good at can really help you, but only for a short time. In the summertime, when we're out kiting every day, you feel 100%. But when you're at home the whole winter like, during Corona, you don't get to travel. It's cold, raining, you don't get to kite and get filled up with adrenalin. As extreme athletes, we need that in our lives.

"During Corona, my girlfriend told me: "Man, I don't know what you've turned into, but please do something". So, I started working out. Not like pushing iron, but I started indoor rowing. It's really boring, but it gives me what I need.

"My alarm goes off every morning at 5.21am, and I sit up in bed (not that I want to). Then I put on my training shirt, shorts, and shoes, grab my yoga mat and go. If I don't do that every morning, I can really feel the difference in my day.

"I row every morning from 6am-7am, then I come home, drive Marie's daughter to school, and eat breakfast. I experimented with not doing it for a month, just to see if it was this or a third party that was putting me in such a good headspace. But it was exercise, and it was me getting out there and pushing myself cardio-wise. There were stages when I'd think: "I can't go any further because that's not what my body wants," but I'd row another 2km to see what happens. I would want to scream, puke, and run from all my responsibilities – it was so far out that I would rather die than have the feeling I was having at that moment. But a minute later, when you regain control of your breathing and your muscle tension, you're taken to a different place. For me personally, it really helps to just go there. Move my body. Do something.

"Every Thursday, there's no rowing class, but I wake up at the same time, go for a run, go for a swim, or Marie and I will go for a walk in the forest or something. It feels good. I mean, holy bananas, I went to a party until 4am a few weeks ago and felt terrible for four days after. It was such a shock to my body. It was crazy fun," Nick admits, "but you know, I'm ok with not doing that again".

Nick with close mate Graham Howes, in Capetown. Photo Craig Kolesky.